I use learning stations in my classroom to differentiate my instruction. I don’t differentiate in the sense that different students are doing different tasks on the same skill; I actually have different students in my room working on different skills at the same time.

Everyone does not work at the same pace. Some of us take longer than others to learn a skill. Some of us require more practice than others. And some of us are missing tools in our academic arsenal needed to complete the grade level work (I call these prerequisite skills) and we need to go back and learn those skills first so that we can do the grade level work.

For example, you can’t do long division if you don’t know your times tables. You can’t add fractions if you don’t know how to find the common denominator. And you can’t graph a linear equation if you don’t understand slope.

As the class is moving through the curriculum, the students with the needs that I mentioned in the paragraphs above cannot pace with the rest of the students and they will fall behind. Rather than abandoning these students, or forcing them to move ahead knowing that they can’t do the grade level work, I remediate them so that they can be successful.

So I build learning stations to remediate my students, and teach them these prerequisite skills – or to give them extra practice

Learn more about creating and using learning stations

The Traditional Model

I was not always this way. I used to teach math using the traditional model. Which meant I paced everyone, together, and all the students moved through the same material at the same time, receiving the same amount of practice.

Even though I knew that everyone learns different skills differently,

I still treated all my students the same.

And when many of my students did not master a skill, I retaught it to the whole class, even though there were many in the room who did not require a reteach – they were ready to move on.

I retaught the skill even though some of the students couldn’t do the work because they hadn’t learned the previous skills that they needed to have mastered to complete the current work. I simply retaught the skill, the same way, to everyone, expecting a different result.

Eventually, I felt that we had spent too long on that skill, and I moved the whole class onto the next skill, even though there were still several students who had not mastered the previous skill.

I’m sure that the students who hadn’t understood the previous skill, and were now being drug into another skill that they wouldn’t understand, had to feel ‘given up on,’ and perhaps ‘hopeless of ever learning math.’

Besides this feeling of abandonment, many math concepts build upon each other. So I was now trying to teach these students math concepts that they were not prepared to learn, because I hadn’t given them the time or practice that they required to learn the prerequisite skills (or I didn’t bother to reteach them those skills that they needed but hadn’t received in previous years).

Was I a good math teacher?

Yes, many of my students felt that I was not a good math teacher. They said that I wasn’t helping them, or I never answered their questions. At the time, I argued that I was teaching very effectively, they just weren’t learning – but we had to get through the curriculum and I couldn’t hold the entire class back on their account. But looking back, I now see why they felt that way. And I have to agree with them. I had not invested in building them up. I had not allowed them to wrestle with the material for as long as they needed, until they finally grasped the material. I just moved them along, exposing them to the entire year’s coursework without ever allowing them to master any of it.

Epiphany

One day, I had an epiphany that changed the way I delivered my math instruction.

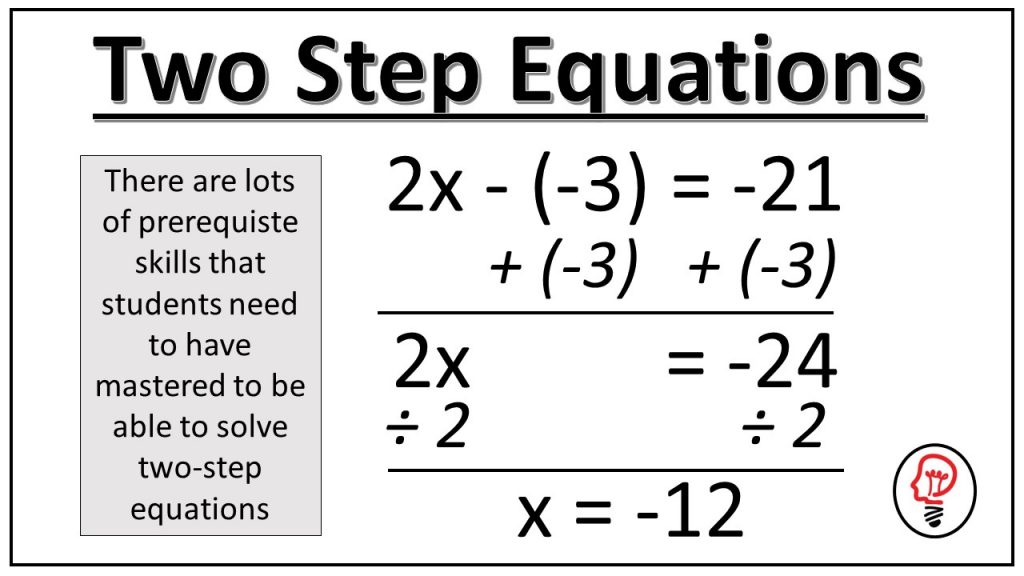

I was teaching two-step equations.

Two-step equations is a very advanced skill because it involves performing a series of tasks in the correct order to arrive at the correct answer.

After delivering my instruction on how to solve two-step equations I gave the students some independent practice and began circulating the classroom, helping students as they did their work. I noticed that most of the students were not able to do the work. But even more intriguing to me than that was that many of the students were struggling at different steps in the process. Some couldn’t do the first step because they hadn’t mastered adding or subtracting integers. Others couldn’t do the next step because they didn’t know how to multiply or divide integers. And some didn’t know the right steps for one or two-step equations.

I realized that if the students were going to be able to complete a two-step equation problem, they had to master all of these prerequisite skills.

The Remedy

So I decided that I was going to build a learning station for each skill. And I would organize the stations in order, so that they built upon each other. And as the students mastered one station, they would be promoted to the next, each time becoming one step closer to mastering the standard.

I determined that success was going to be measured in growth, not in getting through the curriculum.

I also began to think about how we learn something. Since each station was going to have to serve the role of teaching the skill, and giving sufficient feedback.

Beyond this, I began to realize the value of immediate feedback, and giving someone as long as they needed to learn something – because there is power in them gaining confidence as they truly grasp concepts.

Don’t forget to PIN me!

The Assembly Line Versus the Ladder

Previously, my class looked like an assembly line. Where all the students were lumped together, and moved along the same path at the same time, receiving the exact same treatment. Even though I knew that not everyone is the same, and we all have different needs.

Now, my class looks like a ladder (or a bunch of ladders). Where everyone is taking steps as they master a skill, moving towards the top – which is mastering a standard. Not everyone is in the same place, but everyone is making progress, and everyone can see their progress.

With assembly lines, defective pieces are discarded. And that’s exactly what I was doing to my students. If they didn’t pace with the majority of the class they were marginalized, abandoned, and left behind. Now they are remediated, and shown that they matter because I’m not giving up on them. Instead, I’m giving them the tools that they need to succeed.

If you have enjoyed this post, share it with your friends

Join Me on a Journey to Reach All Your Students

Download the free cheat sheet to learn more about Learning Stations.

Click here to download the free cheat sheet